Scientists at Monash University have created a tiny fluid-based chip that behaves like neural pathways of the brain, potentially opening the door to a new generation of computers.

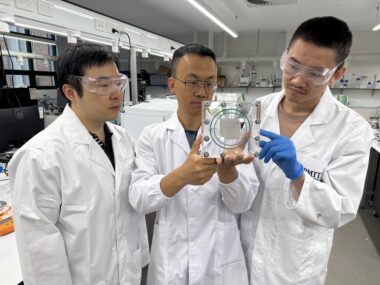

Roughly the size of a coin, the chip was built from a specially designed metal-organic framework (MOF), and channels ions through tiny pathways, mimicking the on/off switching of electronic transistors in computers.

But unlike conventional computer chips, it can also “remember” previous signals, mimicking the plasticity of neurons in the brain.

Co-lead author Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor and ARC Laureate Fellow, Professor Huanting Wang, Deputy Director of the Monash Centre for Membrane Innovation, highlighted the potential of engineered nanoporous materials for next-generation devices.

“For the first time, we’ve observed saturation nonlinear conduction of protons in a nanofluidic device. This opens up new opportunities for designing iontronic systems with memory and even learning capabilities," Professor Wang said.

“If we can engineer functional materials like MOFs just a few nanometres thick, we could create advanced fluidic chips that complement or even overcome some limitations of today’s electronic chip."

To demonstrate its potential, the team built a small fluid circuit with multiple MOF channels. The chip’s response to voltage changes mimicked the behavior of electronic transistors, while also showing memory effects that could one day be used in liquid-based data storage or brain-inspired computing systems.

Co-lead author Dr Jun Lu, from the Monash Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, who is currently working as a visiting scholar at the University of California, said the development was the first-of-a-kind and a major step towards computers that think more like humans, using liquid instead of solid circuits.

“Our chip can selectively control the flow of protons and metal ions, and it remembers previous voltage changes, giving it a form of short-term memory,” Dr Lu said.

“What makes our device truly special is its hierarchical structure, which allows it to control protons and metal ions in entirely different ways. This kind of selective, nonlinear ion transport hasn’t been seen before in nanofluidics.”

Read the research paper: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adw7882

MEDIA ENQUIRIES

Courtney Karayannis, Media and Communications Manager

Monash University

P: +61 408 508 454 or [email protected]

GENERAL MEDIA ENQUIRIES

Monash Media

P: +61 3 9903 4840 or [email protected]

For more experts, news, opinion and analysis, visit Monash News.